Hummer has been slang for hummingbird since 1868, when Titus Fey Cronise used the term in The Natural Wealth of California. For birders, the term refers to one of dozens of species of hummingbirds rather than obscenely big cars or bedroom frolics. Having spent some time in Abbey Country with birders, I often forget it has any other connotation.

Cochise County, May 12, 2012

For a couple of months each spring and a couple of months each summer, dozens of volunteers gather in Abbey Country to observe and band local and migratory hummingbirds. Banding takes place at SABO (Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory) and at the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. SABO is administered by Sheri L. Williamson, who wrote the Peterson’s Guide to Hummingbirds, and her husband, Tom Wood.

Banding takes place at the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area on Saturdays from 4-6 p.m. in April and May, July and August. The event is free and interactive.

4:00 p.m. The bird trap is set to catch a hummer. A bird enthusiast holds a remote control device about twenty feet away from the trap. When a hummer starts to feed, down goes then netting. Sheri Williamson waits nearby at a processing table to band caught birds and release them.

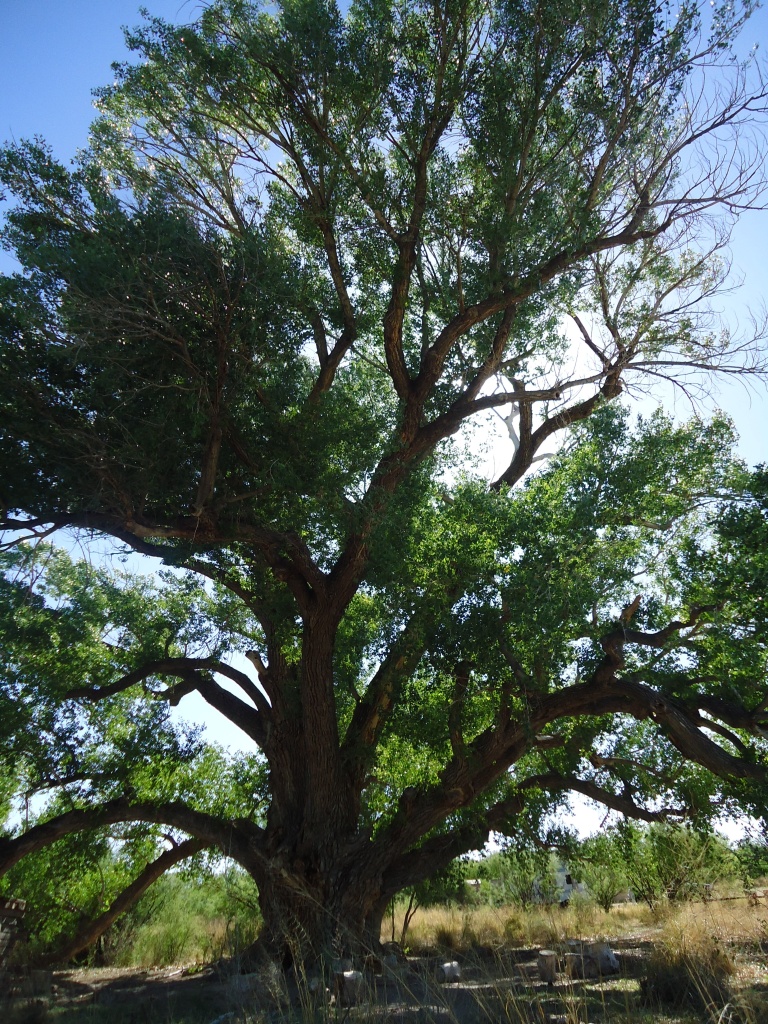

This giant cottonwood is just feet away from the trap. Many hummers nest in this tree. During the two hours this Saturday, they flew out of the tree and right past the trap to sip nectar from ocotillo and other blooming desert flowers.

4:15: Tom Wood waits near the trap. The previous week at San Pedro, SABO caught and banded twenty hummers! So far, not one has gone near the trap.

The minutes ticked by. About a dozen children in the crowd continued to wait with more patience than I thought possible. The afternoon breeze along the San Pedro was warm, and the calls of several kinds of birds dotted the relative silence. Tom and Sheri speculated that the birds weren’t coming to the trap for two main reasons: They were already on their nests, and the nectar of the blooming ocotillo was preferable to the clear sugar water in the feeders.

The hummers that hang around San Pedro in April and May are mostly local, and many are on their nests by the beginning of June. The hummers in San Pedro over the summer tend to be migrants from Mexico, some bound as far as Montana and beyond.

Finally, just as the crowd was beginning to give up, a cheer came from around the trap. Tom carried the black-chinned hummingbird in a small net cage from the trap to Sheri’s processing table.

Hummers, according to Sheri, have excellent spatial memory. They remember what flowers they visited and when. She is often asked if the banding process harms the birds. “They are incredibly brave and tough little birds,” she says, “They are emotionally durable.” They are not physically traumatized, of that she’s sure. It takes one to two minutes to process a bird, and they won’t leave birds waiting for more than ten minutes. The birds are handled gently and given a drink when the banding is complete. Sheri says she’s caught some birds up to sixteen times, five times in one year. Given their intelligence, she thinks, they wouldn’t return if they were emotionally traumatized. She says, in fact, that it’s difficult to emotionally traumatize a wild animal. Given the intelligence of the average hummer, the birds tend to go into a “this is weird…what happens next” mode, playing possum. Most birds take the drink at the end, and this is their way of saying that they’re okay with the process.

The band goes on the leg. This banding number goes into a national database that helps SABO and other groups track the migratory habits and numbers of hummers. The pliers Sheri uses were made especially for the purpose by a retired machinist. These are heirloom, she says, and will be passed down to another bird bander when she retires.

Sheri determines that this bird is male. Susan Ostrander, the SABO spokeswoman for the afternoon, explains that birds such as this are “dead beat dads”. Many species of birds mate at least for the season, and the male helps build and guard the nest as well as feed the hatchlings. Not hummers. Once the eggs are fertilized, the couple separates permanently, and the woman is on her own. Hummers are loners, as well, not migrating in groups but preferring to go it alone. Once the female’s hatchlings leave the nest, she flies solo once again.

Based on the size of his bill, Sheri concludes that the bird hatched last year. She also notes the “perfectly clean, uniformly green back”, and explains that black-chins molt partially in the fall, partially in the spring. If he were older, some of his feathers would have turned blue and be broken at the tips.

Sheri explains her process to the crowd as the dozen patient children wait for a chance to hold the hummer.

Using a straw, Sheri blows aside the hummer’s feathers. This allows her to assess the bird’s percentage of body fat, which is too high for him to be a local bird. He’s a migrant, Sheri concludes, “one of the millions that uses the San Pedro as a highway to get up from Mexico to the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, into western Canada and even Alaska.”

Sheri (left) and Kathy (right) continue to process the young, male, migrant black-chinned hummer as one young bird enthusiast takes it in.

Right after the exam, the hummer gets a drink. It’s important to note that red dye should never, ever be used to feed hummingbirds. It poisons them.

The banding and exam are complete. Just about all that’s left now is his release. But before that, Susan whips out a stethoscope so that the children can hear his racing heart.

Their patience rewarded, the children wait to hear the hummer’s heartbeat. One of them will get to release the bird.

When birders arrive at San Pedro house between three and four to prepare for the banding, they are given a number. First come first served: if your number comes up you may hold the hummer before it’s released. Today, since there was only one capture, adults with numbers gave them to the waiting children.

According to Ostrander, some say the hummer’s heartbeat sounds like wind blowing through the trees, others say it’s like a cat purring. One man, she remembers, said it sounds like a Harley on a distant hill. Twelve hundred beats in a minute is not unusual.

Ostrander places the hummer in this boy’s hand as the crowd watches. Surprisingly, he does not fly away.

Since the hummer seems to want to hang out with the children, Ostrander transfers him from one child’s hands to the next. The atmosphere becomes hushed; the children even more reverent.

6:00 p.m. Sheri and the crowd wait for the hummer to fly away. He’s allowed Susan to transfer him four times, which is most unusual.

Then, faster than my camera can capture, the hummer is airborne, flying toward his superhighway and his summer home.

Gr8 job Carolyn…felt like I was there! It really captured the total experience and a few hummer’s too! http://www.arizonasunshinetours.com with http://www.sabo.org